This album is fucked. Filthy. Disgusting. Disturbing. Utterly unpleasant in all aspects. Anyone chomping at the bit after hearing those descriptors is the perfect audience for A Hell for Horses, the first full-length from Syracuse quartet goner., who here far surpass their early output and deliver something truly memorable. This is dirty, pus-encrusted metallic hardcore, occasionally leaning toward straightforward grind, sometimes galloping on a propulsive thrash chug, often breaking into slamming halftime with the high-pitched guitar squeals of modern metalcore. But this mess of genre assimilations doesn’t translate to a lack of focus or quality in the music itself, for every second of A Hell for Horses is smeared with the chunky Ragu blood of rotting horse corpses, the stinking visceral slop constantly dripping from the blasting assaults in the form of gritty effects sludge and decayed harsh noise currents. goner.’s effective and purposeful use of these unsettling motifs extends to the lyrics as well, and when I consider those in conjunction with the instrumentals, it’s impossible not to see this album as a spiritual successor to Gaza’s I Don’t Care Where I Go When I Die, which also dealt heavily in themes of gore and violence both musically and lyrically (“Sire,” among others: “I’ll break your colt’s legs / I’ll snag and spill your deer on the fence / I’ll find your tears / I will corral you into the cattle hammer”). C.Z., the band’s vocalist and lyricist, also embodies a persona of someone who stumbles on the lowest level of humanity, leaning heavily into a shock-value satire that results in some twisted and darkly hilarious lines—”Cumsick”: “que laughter [sic] / i left a bag of dog hair at your door and i still cant pet you / i left my fingernails, i’ll scratch your back”—again both complementary to the intensity of the music and reminiscent of Jon Parkin’s most bleakly ironic howls (particularly in “A Hard Left on Burnett” and “Krokodil Tears”). I doubt anyone would look at the red-bathed mayhem on the cover and expect anything less than the musical equivalent of a captive bolt gun shot straight in the temple, but A Hell for Horses burrows so far into the blood-soaked trash bin of humanity that its brutality will most likely exceed any expectation.

This album is fucked. Filthy. Disgusting. Disturbing. Utterly unpleasant in all aspects. Anyone chomping at the bit after hearing those descriptors is the perfect audience for A Hell for Horses, the first full-length from Syracuse quartet goner., who here far surpass their early output and deliver something truly memorable. This is dirty, pus-encrusted metallic hardcore, occasionally leaning toward straightforward grind, sometimes galloping on a propulsive thrash chug, often breaking into slamming halftime with the high-pitched guitar squeals of modern metalcore. But this mess of genre assimilations doesn’t translate to a lack of focus or quality in the music itself, for every second of A Hell for Horses is smeared with the chunky Ragu blood of rotting horse corpses, the stinking visceral slop constantly dripping from the blasting assaults in the form of gritty effects sludge and decayed harsh noise currents. goner.’s effective and purposeful use of these unsettling motifs extends to the lyrics as well, and when I consider those in conjunction with the instrumentals, it’s impossible not to see this album as a spiritual successor to Gaza’s I Don’t Care Where I Go When I Die, which also dealt heavily in themes of gore and violence both musically and lyrically (“Sire,” among others: “I’ll break your colt’s legs / I’ll snag and spill your deer on the fence / I’ll find your tears / I will corral you into the cattle hammer”). C.Z., the band’s vocalist and lyricist, also embodies a persona of someone who stumbles on the lowest level of humanity, leaning heavily into a shock-value satire that results in some twisted and darkly hilarious lines—”Cumsick”: “que laughter [sic] / i left a bag of dog hair at your door and i still cant pet you / i left my fingernails, i’ll scratch your back”—again both complementary to the intensity of the music and reminiscent of Jon Parkin’s most bleakly ironic howls (particularly in “A Hard Left on Burnett” and “Krokodil Tears”). I doubt anyone would look at the red-bathed mayhem on the cover and expect anything less than the musical equivalent of a captive bolt gun shot straight in the temple, but A Hell for Horses burrows so far into the blood-soaked trash bin of humanity that its brutality will most likely exceed any expectation.

Month: November 2020

Review: Duncan Harrison & Ian Murphy – Slow Lightning (Sham Repro, Nov 2)

If yesterday’s review of Hypnagogic’s sprawling text-sound tape compilation wasn’t enough to sate your voracious appetite for surreal slur and vocal skronk, look no further than this new LP from Brighton fluxers Duncan Harrison and Ian Murphy, a half-collaborative half-split release that digs its knuckly fingers deep into the roots of both the human and the natural world. Side A of Slow Lightning features a series of delirious sketches by Harrison, the field and improvised recordings captured and assembled over the course of the last five years into this “final” result, which sheds the often claustrophobic interiority and domesticity of last year’s peerless Nothing’s Good for a much looser, eclectic, and organic palette that still retains its predecessor’s predilection for nonverbal poetry, the intrigue and sublimity in the extraneous everyday. Stuttering, spectral loops of unusual utterances, rustling leaves and tinkling wind ornaments, gasps and grunts, afterthoughts, a sighing piano lament, all culminating episodically in a finale of violent turntable mayhem reminiscent of his Music from Amplified Flexible Discs tape on Cardboard Club earlier this year. Murphy’s “side” (which also features Harrison) is much more speech-reliant, built upon endless knots and layers of spliced tape, out-of-context muttering, chattering crowds, honking geese, and its own brand of record-and-stylus abuse, here manifesting as something much sparser and gentler. A thoroughly enthralling expressionist sound-canvas from these irreverent partners in crime.

If yesterday’s review of Hypnagogic’s sprawling text-sound tape compilation wasn’t enough to sate your voracious appetite for surreal slur and vocal skronk, look no further than this new LP from Brighton fluxers Duncan Harrison and Ian Murphy, a half-collaborative half-split release that digs its knuckly fingers deep into the roots of both the human and the natural world. Side A of Slow Lightning features a series of delirious sketches by Harrison, the field and improvised recordings captured and assembled over the course of the last five years into this “final” result, which sheds the often claustrophobic interiority and domesticity of last year’s peerless Nothing’s Good for a much looser, eclectic, and organic palette that still retains its predecessor’s predilection for nonverbal poetry, the intrigue and sublimity in the extraneous everyday. Stuttering, spectral loops of unusual utterances, rustling leaves and tinkling wind ornaments, gasps and grunts, afterthoughts, a sighing piano lament, all culminating episodically in a finale of violent turntable mayhem reminiscent of his Music from Amplified Flexible Discs tape on Cardboard Club earlier this year. Murphy’s “side” (which also features Harrison) is much more speech-reliant, built upon endless knots and layers of spliced tape, out-of-context muttering, chattering crowds, honking geese, and its own brand of record-and-stylus abuse, here manifesting as something much sparser and gentler. A thoroughly enthralling expressionist sound-canvas from these irreverent partners in crime.

Review: Various Artists – Birdsong from the Lower Branches (Hypnagogic Tapes, Nov 3)

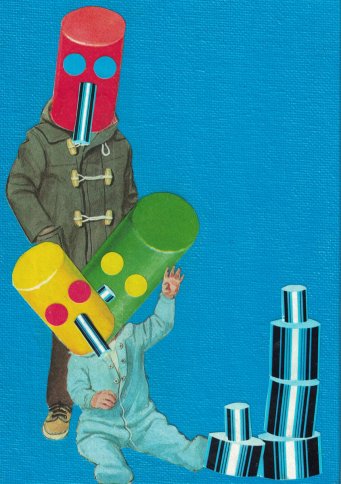

Birdsong from the Lower Branches is an aptly titled collection of artists across the globe who work with voice, utterance, text-sound, and other related areas of study. Another various artists tape that came out earlier this year was Regional Bears’ New Tulips, but even though that splendid compilation already seemed to me to have assembled the full gaggle of usual suspects, the list of artists that contributed the pieces for Birdsong has no crossover whatsoever with that of New Tulips. Yet despite this obvious labor of love being specifically curated to “highlight the many different styles and techniques used in contemporary & experimental vocal work” in addition to the (relative) singularity of the roster, Birdsong still boasts quite a few familiar names, prolific babble-stalwarts that many of the weirdos bothering to check out this tape in the first place: Karen Constance (who also provided the cover collage), id m theft able, Sigtryggur Berg Sigmarsson, Seymour Glass, Ali Robertson. Just halfway through one can already see that the effort to present a diverse survey of creative work was wildly successful; we’re thrown from the jarring tape-switch enjambments of a speech-only track from Eric Mingus, James King’s humbly introduced and spectacularly executed “distillations,” a duet for emergency services siren and a cappella Irish folk song by Mabel Chah, an anxiety-soaked onslaught of gasps and groans from Rising Damp, a surreal post-Super Saturday broadcast from Robertson… the list goes on. A wonderfully eclectic and consistent set of of titillating tidbits.

Birdsong from the Lower Branches is an aptly titled collection of artists across the globe who work with voice, utterance, text-sound, and other related areas of study. Another various artists tape that came out earlier this year was Regional Bears’ New Tulips, but even though that splendid compilation already seemed to me to have assembled the full gaggle of usual suspects, the list of artists that contributed the pieces for Birdsong has no crossover whatsoever with that of New Tulips. Yet despite this obvious labor of love being specifically curated to “highlight the many different styles and techniques used in contemporary & experimental vocal work” in addition to the (relative) singularity of the roster, Birdsong still boasts quite a few familiar names, prolific babble-stalwarts that many of the weirdos bothering to check out this tape in the first place: Karen Constance (who also provided the cover collage), id m theft able, Sigtryggur Berg Sigmarsson, Seymour Glass, Ali Robertson. Just halfway through one can already see that the effort to present a diverse survey of creative work was wildly successful; we’re thrown from the jarring tape-switch enjambments of a speech-only track from Eric Mingus, James King’s humbly introduced and spectacularly executed “distillations,” a duet for emergency services siren and a cappella Irish folk song by Mabel Chah, an anxiety-soaked onslaught of gasps and groans from Rising Damp, a surreal post-Super Saturday broadcast from Robertson… the list goes on. A wonderfully eclectic and consistent set of of titillating tidbits.

Review: Wreck of the Minotaur – A Little Roy One on One Reissue (Tomb Tree Tapes, Oct 31)

I see you ya fuckin’ posh fucker… I’ve got yous here a can o’ big fuckin’ money Stella…

Is there a spoken introduction to an album that is a more iconic and anticipatory indicator of incoming chaos than this, the funny yet vaguely threatening ramble tumbling into the feedback and unhinged screaming that begins opening track “Big Money Stella” on A Little Roy One on One, Wreck of the Minotaur‘s only release. With all of the forgotten 00s scenecore that prolific collector’s edition label Wax Vessel has been putting out, I figured it would be them who got their hands on the rights to reissue this brief but beloved five-song EP, but instead the long-overdue reintroduction of the London band’s flash-in-the-pan masterpiece has been handled by small Nanaimo, B.C. tape label Tomb Tree. Unsurprisingly, the small run of cassettes printed sold out almost immediately, but the repackaged version (there doesn’t seem to have been any remastering or other alterations done) is available for name-your-price download on Bandcamp, complete with an appropriately gruesome revamped version of the original cover art. My hope is that most of you have heard this already, but if not now is certainly the time; WotM’s flawless onslaught of complex, technical riffs and grooves; both off-kilter, ersatz math breakdowns and traditional mosh slams; some of the most (appealingly) virtuosic hardcore drumming ever laid to tape; expert control of dynamics; and a remarkably well-assimilated sample from the film adaptation of American Psycho in “Hard Bodies Are Everywhere! Hand Me My Blade!”: Patrick’s distressed and ultimately useless confession to his lawyer is accompanied by snapping snare and a quirky bass lick before the instrumental descends into complete chaos once more. There are even some well-placed violins in unforgettable closer “My Sweet Annabella I’m Not Coming Home,” (and if that alone doesn’t sell you, the track was also included in my Breakdown Bonanza mix). A Little Roy One on One is both inextricably a product/artifact of its time and a completely timeless slice of fucked-up genius. I hope these surprise rereleases keep coming because I love being able to write about things I love that I missed the ability to review due to my youth; fingers crossed for Black Market Activities to realize that a vinyl press of I Don’t Care Where I Go When I Die for its fifteenth anniversary next October would be an absolute cash-cow, and/or that whoever is putting out a Hayworth discography release does it soon.

Review: eric – We Can’t Be Stopped (Trading Wreckage, Oct 31)

Review: Potion – Cemetary (self-released, Oct 31)

This is coming a bit late since Cemetary [sic] is clearly a heavily Halloween-themed release, but this week my mind was occupied by… other things. And anyway, this amazing cover art and its tremendously well done object-font used for the band’s name are enough for this short album to be appreciated year-round. This is the closest thing Potion has come to a full-length since their debut on a split tape with Car Made of Glass early last year (both bands consist of former members of tech-sass quartet Antarctica, whose penchant for both fragmented interlude abstractions and lunatic-hardcore certainly lives on, uniquely, in each), and since Bandcamp user horsesofallston commented, “please please please release a full-length. no other humans can make these noises. (trust me I’ve tried),” but it’s not new material. In fact, all six tracks were recorded long before the project’s official declaration of existence: the first three in 2016, with Cammie Berkel on vocals and Quade Ross on drums, and the final three in 2017 with Quentin Salmon lending some piercing screams (which end up sounding sort of like Chip King’s thing, but way better and not annoying) to the first of the two “Dog Jail” tracks. Hunter Petersen is the constant member in all of these slabs of dizzying technicality, which makes the marked eclecticism of the short set even more astounding: “Trib.al/tech_support” and the ensuing two fellow shorter tracks are a nightmarish hell-scapes of tortured shrieks and relentless shred-blasts, while the title cut and “Dog Jail 2: Deja Blue” are like slightly unhinged 80s stadium-jam worship, the latter complete with harmonica. One for the ages.

This is coming a bit late since Cemetary [sic] is clearly a heavily Halloween-themed release, but this week my mind was occupied by… other things. And anyway, this amazing cover art and its tremendously well done object-font used for the band’s name are enough for this short album to be appreciated year-round. This is the closest thing Potion has come to a full-length since their debut on a split tape with Car Made of Glass early last year (both bands consist of former members of tech-sass quartet Antarctica, whose penchant for both fragmented interlude abstractions and lunatic-hardcore certainly lives on, uniquely, in each), and since Bandcamp user horsesofallston commented, “please please please release a full-length. no other humans can make these noises. (trust me I’ve tried),” but it’s not new material. In fact, all six tracks were recorded long before the project’s official declaration of existence: the first three in 2016, with Cammie Berkel on vocals and Quade Ross on drums, and the final three in 2017 with Quentin Salmon lending some piercing screams (which end up sounding sort of like Chip King’s thing, but way better and not annoying) to the first of the two “Dog Jail” tracks. Hunter Petersen is the constant member in all of these slabs of dizzying technicality, which makes the marked eclecticism of the short set even more astounding: “Trib.al/tech_support” and the ensuing two fellow shorter tracks are a nightmarish hell-scapes of tortured shrieks and relentless shred-blasts, while the title cut and “Dog Jail 2: Deja Blue” are like slightly unhinged 80s stadium-jam worship, the latter complete with harmonica. One for the ages.

Review: Akio Suzuki & Aki Onda – gi n ga (Hasana Editions, Oct 25)

In their hopefully ongoing series of live albums (of which there are three so far, all released on different labels), Akio Suzuki and Aki Onda always evoke strange and wonderful worlds to escape into, a distracting immersion that’s exactly what I need after this hell-week. The two Japanese sound artists operate in only slightly overlapping areas in their solo careers, but together their auditory instincts are nothing less than symbiotic, and the freshly released gi n ga is, unsurprisingly, yet another example of this consistently fruitful creative collaboration. The recordings that comprise what I believe is only Hasana Editions’ second CD are sourced (in order) from June 2014, April 2017, and May 2014; thus, chronologically, this collection falls both between and ahead of the preceding ma ta ta bi (ORAL, 2014) and ke i te ki (Room40, 2018), which were compiled with material from 2013 and 2015, respectively. Despite that connection, however, it’s difficult for me to say whether there’s any meaningful linear trajectory of the duo’s improvisational output; to me it seems like the two musicians are so reverently devoted to the particular situation, circumstances, location, context, etcetera etcetera of a performance that they will always end up with something unique, regardless of what came before. You’ll certainly pick up on each of their preferred palettes: in the opener, “na ki sa,” alone we hear a fuzzy tape loop of crashing waves, no doubt Onda’s doing, while Suzuki’s unmistakable Analapos whirls its spectral song in the background. I couldn’t tell who contributed the vocal elements or the almost-rhythmic flute stomp in this piece, the latter of which had me unconsciously tapping a loose tribal beat underneath it. The following two tracks tilt further toward the abstract and serve up more of the texturally lush yet slightly brooding, even ominous soundscapes that made ke i te ki so enrapturing. Of these, the concluding “sa na ki” (you may notice that the titles are simply three of the possible combinations of the original syllables) is probably my favorite, unfolding like a director’s cut of the daily activities on the floor of a miniature industrial plant.

In their hopefully ongoing series of live albums (of which there are three so far, all released on different labels), Akio Suzuki and Aki Onda always evoke strange and wonderful worlds to escape into, a distracting immersion that’s exactly what I need after this hell-week. The two Japanese sound artists operate in only slightly overlapping areas in their solo careers, but together their auditory instincts are nothing less than symbiotic, and the freshly released gi n ga is, unsurprisingly, yet another example of this consistently fruitful creative collaboration. The recordings that comprise what I believe is only Hasana Editions’ second CD are sourced (in order) from June 2014, April 2017, and May 2014; thus, chronologically, this collection falls both between and ahead of the preceding ma ta ta bi (ORAL, 2014) and ke i te ki (Room40, 2018), which were compiled with material from 2013 and 2015, respectively. Despite that connection, however, it’s difficult for me to say whether there’s any meaningful linear trajectory of the duo’s improvisational output; to me it seems like the two musicians are so reverently devoted to the particular situation, circumstances, location, context, etcetera etcetera of a performance that they will always end up with something unique, regardless of what came before. You’ll certainly pick up on each of their preferred palettes: in the opener, “na ki sa,” alone we hear a fuzzy tape loop of crashing waves, no doubt Onda’s doing, while Suzuki’s unmistakable Analapos whirls its spectral song in the background. I couldn’t tell who contributed the vocal elements or the almost-rhythmic flute stomp in this piece, the latter of which had me unconsciously tapping a loose tribal beat underneath it. The following two tracks tilt further toward the abstract and serve up more of the texturally lush yet slightly brooding, even ominous soundscapes that made ke i te ki so enrapturing. Of these, the concluding “sa na ki” (you may notice that the titles are simply three of the possible combinations of the original syllables) is probably my favorite, unfolding like a director’s cut of the daily activities on the floor of a miniature industrial plant.

Review: Pantea – Things (Active Listeners Club, Oct 23)

Active Listeners Club, a new netlabel “dedicated to active listening” through releasing abstract experimental music by Tehran’s sound artists and forward-thinking musicians, caught my attention early this month with the bizarre sonic palette, complete contextual obscurity, and eye-catching cover template of their inaugural release: Ben & Jerry’s Formant Fry (the collaborative musical debut from label founders and operators Ramtin Niazi and PARSA), an impressive array of sensory-overload sample collage, some of the contents of which appear to be extracted from video games. Things, ALC’s second offering, is also Tehran artist pantea’s second—that is if you don’t count AA0011, a brief set of two tracks put out digitally in 2018. I enjoyed this one a great deal more than the preceding everydaymeal, which came out on Czsaszka earlier this year; here the Iranian musician and photographer largely leaves the recognizability of the real word behind, instead delving deep into granular dissections and dense, physical arrangements of high-velocity tones and razor-sharp remnants, transporting us to the inside of an atom smasher gone haywire. The impossibly agile contortions of “Patu (blanket)” rival the impressive sound design of glitch-storm experimenters like Florian Hecker or Jeff Carey, but the following “N.E.W.S & ESX,” and the mangled carcass of a dance track it tosses in our laps, reminds everyone that pantea has her hands much deeper in the innards of the cadaver of electronic music as all of these talented sound-surgeons perform its autopsy—all the way up to the elbows, in fact; I think club music would be located pretty deep in the chest cavity.

Active Listeners Club, a new netlabel “dedicated to active listening” through releasing abstract experimental music by Tehran’s sound artists and forward-thinking musicians, caught my attention early this month with the bizarre sonic palette, complete contextual obscurity, and eye-catching cover template of their inaugural release: Ben & Jerry’s Formant Fry (the collaborative musical debut from label founders and operators Ramtin Niazi and PARSA), an impressive array of sensory-overload sample collage, some of the contents of which appear to be extracted from video games. Things, ALC’s second offering, is also Tehran artist pantea’s second—that is if you don’t count AA0011, a brief set of two tracks put out digitally in 2018. I enjoyed this one a great deal more than the preceding everydaymeal, which came out on Czsaszka earlier this year; here the Iranian musician and photographer largely leaves the recognizability of the real word behind, instead delving deep into granular dissections and dense, physical arrangements of high-velocity tones and razor-sharp remnants, transporting us to the inside of an atom smasher gone haywire. The impossibly agile contortions of “Patu (blanket)” rival the impressive sound design of glitch-storm experimenters like Florian Hecker or Jeff Carey, but the following “N.E.W.S & ESX,” and the mangled carcass of a dance track it tosses in our laps, reminds everyone that pantea has her hands much deeper in the innards of the cadaver of electronic music as all of these talented sound-surgeons perform its autopsy—all the way up to the elbows, in fact; I think club music would be located pretty deep in the chest cavity.

Review: Kiera Mulhern – De ossibus 20 (Recital, Oct 23)

The first track on De ossibus 20, sound artist Kiera Mulhern’s debut full-length, is like a slow submerging into a bath of perfectly warm water. It proceeds through a murk of churning haze with ease: languid spin cycle drone, ghostly chatter, tactile shift. The extra-soft rug is soon pulled from under our feet, however, for Mulhern’s own voice finally surfaces after an unceremonious snatching-away of that fragile fog-scape, rising in layers of wavering vocalizations that twitch with distortion, skips, and shudder as they begin to thicken and coalesce before ultimately ceasing to let some muffled coffee shop ambience to close out the track (McCann describes the LP as “burying a microphone in a book”; I’m not sure if he meant it literally, but here it certainly sounds as if we’re closed out of something yet still near enough to hear it). Mulhern’s superb ear for the extremely abstract poetics of the voice-in-place is no fluke, for the remaining tracks on De ossibus 20 continue to offer up a plethora of delightful texture-stew, from the seething, organic effervescence and lush garble of “Self-auscultation 5/24/20” to the paranoid whispers and ambiguous spatiality of “Sow”; from the hair-raising sound-web and unfinished statements of “Signs in the memory” to the deeply immersive sonic environment and tentatively blown recorders of the concluding “Syrinx.” Works that are truly abstract while also feeling extremely intimate are rare, but Mulhern’s singular explorations, despite their constant elusiveness, strike emotional chords far, far below one’s conscious radar.

The first track on De ossibus 20, sound artist Kiera Mulhern’s debut full-length, is like a slow submerging into a bath of perfectly warm water. It proceeds through a murk of churning haze with ease: languid spin cycle drone, ghostly chatter, tactile shift. The extra-soft rug is soon pulled from under our feet, however, for Mulhern’s own voice finally surfaces after an unceremonious snatching-away of that fragile fog-scape, rising in layers of wavering vocalizations that twitch with distortion, skips, and shudder as they begin to thicken and coalesce before ultimately ceasing to let some muffled coffee shop ambience to close out the track (McCann describes the LP as “burying a microphone in a book”; I’m not sure if he meant it literally, but here it certainly sounds as if we’re closed out of something yet still near enough to hear it). Mulhern’s superb ear for the extremely abstract poetics of the voice-in-place is no fluke, for the remaining tracks on De ossibus 20 continue to offer up a plethora of delightful texture-stew, from the seething, organic effervescence and lush garble of “Self-auscultation 5/24/20” to the paranoid whispers and ambiguous spatiality of “Sow”; from the hair-raising sound-web and unfinished statements of “Signs in the memory” to the deeply immersive sonic environment and tentatively blown recorders of the concluding “Syrinx.” Works that are truly abstract while also feeling extremely intimate are rare, but Mulhern’s singular explorations, despite their constant elusiveness, strike emotional chords far, far below one’s conscious radar.